Infection-Control-First Hospital Design: How Architecture Reduces HAI in Indian Healthcare Facilities

The Design Problem Behind Hospital-Acquired Infections

Hospital-Acquired Infections (HAIs) are typically blamed on human behavior—hand hygiene lapses, protocol breaches, staff non-compliance. Yet the uncomfortable truth is that many HAIs are designed into facilities long before the first patient arrives. Your infection control problem isn’t just a staffing issue; it’s fundamentally an architectural one.

In India, where a single central-line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) costs ₹2-5 lakhs in direct treatment expenses and extends ICU stays by 7-10 days, the financial burden is staggering. One HAI can erase the profit margin from 5-10 uncomplicated admissions. Even modest HAI rates transform operationally successful departments into financial liabilities. Yet most hospitals respond by adding compliance officers and training programs while leaving the physical environment—the actual source of transmission—completely untouched.

Four Architectural Contributors to Cross-Infection

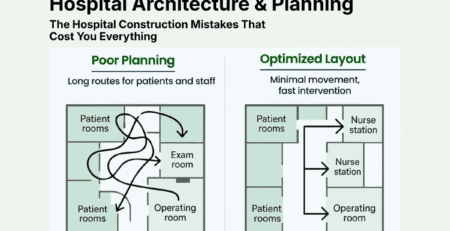

1. Poor Zoning and Flow Design

Clean and dirty traffic paths intersecting creates predictable contamination. When housekeeping wheels a soiled linen trolley down the same corridor your OT trolley uses 30 minutes later, aerosolized particles settle on surfaces. You’ve undermined ₹50,000 of infection control training with a corridor design choice that cost nothing to get right five years ago.

Common failures:

- Shared corridors for patients, waste trolleys, food service, and sterile supplies

- Through-traffic passing through OT corridors or ICU access areas

- Soiled utility rooms positioned adjacent to clean storage or food staging

The fundamental test: Can you trace clean and dirty material flows on your floor plan without them ever crossing? If not, you’ve designed in cross-contamination.

2. Wrong Surface Materials (Silent Pathogen Reservoirs)

Porous flooring absorbs spills and harbors bacteria in microscopic voids. Grout lines in tiled floors create protected microenvironments for biofilm formation. Laminate countertops chip at edges, creating crevices that resist all cleaning. Painted drywall degrades under repeated chemical disinfection, developing rough surfaces that trap pathogens.

These materials don’t just look dirty—they become permanent microbial ecosystems. Staff can scrub daily with aggressive disinfectants, but the material itself defeats their efforts.

3. Inadequate Air Management

Insufficient air changes per hour, poor pressure differentials, or HVAC systems that recirculate air from isolation zones seed entire departments with contamination. The invisible threat manifests weeks later as surgical site infection clusters, by which point establishing causation is impossible. You blame technique, never suspecting your HVAC design is the culprit.

4. Excessive High-Touch Contact Points

Manual door handles, push plates touched 50 times per shift, faucet knobs requiring grip before handwashing, elevator buttons used by hundreds daily—every unnecessary touch is a potential transmission event. Yet most hospital designs create dozens of these contact points because “that’s how we’ve always done it.”

The Financial Case for Infection-Control-First Design

The predictable boardroom objection: “Antimicrobial flooring, touchless fixtures, seamless coving—that’s expensive capex we can’t justify.”

This reveals a fundamental misunderstanding. The question isn’t upfront cost; it’s total cost of ownership over the facility’s 20-25 year life, including operational expenses and avoided HAI costs. When properly calculated, IPC-first design delivers among the highest ROI of any hospital investment.

Real-World Cost Comparison: Patient Room Flooring

Consider a 200-bed facility selecting flooring—one of the most critical infection control surfaces.

Option A – Conventional Vinyl or Ceramic Tile:

- Lower upfront cost: ₹200-350 per sq ft installed

- Grouted joints become bacterial reservoirs

- Requires aggressive chemical cleaning, periodic stripping/rewaxing

- Replacement cycle: 5-7 years

- Higher infection risk from grout lines and micro-gaps

Option B – Seamless Antimicrobial Resin with Integral Coving:

- Higher upfront cost: ₹280-450 per sq ft (15-30% premium)

- Monolithic, non-porous surface with no joints

- Coved edges eliminate 90-degree corners where pathogens accumulate

- Replacement cycle: 12-20 years

- 60-90% reduction in surface bacterial counts

The surface analysis: “Option B costs 25% more. We can’t afford it.”

The lifecycle analysis: “Option B pays for itself in 18-24 months and saves millions over the facility’s life.”

Where Real Savings Materialize

- Deep cleaning labor: Seamless surfaces require lower frequency cleaning, faster completion, less chemical dependency. Annual savings: ₹12-18 lakhs for 200-room facility.

- Cleaning chemicals and water: 30-40% lower consumption without grout penetration needs. Annual savings: ₹3-5 lakhs.

- Room turnover: Faster terminal cleaning (2-2.5 hours vs. 3-4 hours) means higher bed utilization. Revenue opportunity: ₹8-15 lakhs annually.

- Floor replacement: Zero replacements over 10 years vs. 1-2 full replacements. Avoided capex: ₹1.25-3.5 Cr.

The HAI Cost Multiplier

Here’s what changes the entire equation: Preventing just 3-5 HAIs annually can completely fund the IPC-first material premium across your entire facility.

One prevented CLABSI saves:

- Extended ICU stay: ₹1.5 – 2.5 lakhs

- Additional antibiotics and treatment: ₹40,000-80,000

- Repeat diagnostics: ₹15,000-30,000

- Total per CLABSI: ₹2-5 lakhs

This excludes reputational damage, regulatory penalties, litigation risk, and lost revenue from blocked beds.

For a 200-bed hospital with moderate HAI rates, IPC-first design can prevent 20-40 HAIs annually, avoiding ₹40 lakhs – 2 Cr in costs. Suddenly that ₹50 lakh flooring premium looks like the bargain of the decade.

The Critical Design Review Checklist

The greatest opportunity to hardwire safety occurs during design—when plans are still just lines on paper. Every change costs ₹1 at this stage, ₹2-5 during construction, and ₹10 after occupancy (plus operational disruption).

Essential Checkpoints Across Eight Categories

- Zoning & Workflow: Are clean and dirty flows completely segregated? Is through-traffic prohibited in OT corridors, ICU access, and CSSD sterile areas? Can food trolleys and waste trolleys ever meet?

- Operating Theatre & Critical Care: Does your OT enforce strict three-zone design (outer/clean/sterile)? Is the sterile corridor truly dead-end with no through-traffic? Are ICU beds spaced minimum 2.4m apart? Do you have adequate negative-pressure isolation rooms (10% of ICU beds minimum)?

- Hand Hygiene by Design: Are handwashing sinks visible and unavoidable at every patient area entry—not inside rooms, but at thresholds? Are alcohol-based hand rub dispensers positioned every 6-8 meters at natural pause points? Are all clinical area sinks touchless?

- Air Quality & Pressure Control: Do plans specify appropriate air changes per hour (OT: 15-25 ACH, ICU: 12-15 ACH, isolation: 12 ACH minimum)? Are pressure relationships correct—positive in OTs and protective environments, negative in isolation rooms and soiled utility? Do isolation rooms have proper anterooms?

- Surface Materials & Finishes: Are high-touch surfaces specified as antimicrobial copper alloys or coated stainless steel? Are floors seamless with integral cove base (no grout lines)? Are walls moisture-resistant, smooth, non-porous to at least 2 meters height? Is carpet completely prohibited in patient care areas?

- Fixtures & Engineering Controls: Are toilets touchless flush? Are faucets sensor-operated with non-aerating outlets? Are doors in high-traffic areas automatic or equipped with large push plates for elbow operation? Are waste receptacles foot-pedal or sensor-operated?

- Clinical Support Spaces: Does each nursing unit have dedicated clean supply room (positive pressure) and soiled utility room (negative pressure, 10 ACH minimum) that are completely separate? Is there a dedicated medication preparation area with adequate lighting and handwashing?

- Details & Critical Junctures: Are all wall/ceiling penetrations fully sealed with airtight materials? Are access panels gasketed and flush-mounted? Are corners rounded or coved (minimum 1-inch radius)? Are light fixtures sealed and wipeable?

Scoring Your Design

- 90-100% compliant: Strong IPC design foundation

- 75-90% compliant: Acceptable with targeted improvements

- Below 75%: Fundamental redesign required—do not proceed to construction

The Paradigm Shift Required

Traditional approach: Design for function and aesthetics → Build → Hire infection control staff → Train on protocols → React to HAIs when they occur.

Result: HAI rates of 5-8 per 1,000 patient-days, constant struggle, high costs.

IPC-first approach: Design WITH infection control as primary driver → Build infection resistance INTO physical environment → Make safe behavior the easy behavior → Reduce reliance on compliance → Prevent rather than manage HAIs.

Result: HAI rates of 2-4 per 1,000 patient-days, sustainable safety, lower long-term costs.

The difference isn’t better staff. It’s better design.

Conclusion: Where Infection Control Actually Starts

Infection control doesn’t start when a patient develops sepsis, when hand hygiene compliance is measured, or when HAI rates are reviewed in committee meetings.

It starts on the drawing board.

Every surface material you specify, every corridor layout you approve, every HVAC zone you design—these are infection control decisions that determine whether your facility fights pathogens 24/7 without human intervention, or whether even your best staff will struggle against a building designed to enable transmission.

Your walls can fight infections—if you design them to do so. Your floors can resist pathogens—if you choose the right materials. Your airflow can protect patients—if you engineer it correctly.

The technology exists. The materials are available. The financial case is proven. The only question: Will you make these decisions now, when they’re easy and inexpensive, or later, when they’re painful and costly?

Design it right. Build it once. Protect patients forever.

Leave a Reply